The Christian holidays have become largely divorced from their original meanings. In some ways this is helpful, allowing them to be days of universal celebration rather than exclusively serving a single section of our theologically diverse societies. Christmas is these days about giving, gratitude, and reuniting with loved ones, rather than specifically a celebration of Christ's birth. Christ's story encompasses those qualities, but what is celebrated are the shared values rather than the event itself. Though most are aware of Christmas' religious origins - it's right there in the name - the connection is not necessarily made between those origins and the values it now represents. This inevitably leads to the hackneyed complaint that Christmas is just about 'capitalism', which says more about the complainer's inability to understand the value of giving than they might have wished.

Easter is further divorced from the reasons for its Christian celebration than Christmas. In part, this is because the name does not tie in so obviously. According to the Venerable Bede, a seventh-century monk known as the 'Father of English history' for his ecumenical writings, the month of Christ's resurrection was called Eostremonath in Old English, named for the goddess Eostre. The association between the two stuck even after the name of the month changed. Aside from the loose symbolism of eggs to birth, the idea of resurrection has been lost in how we celebrate Easter today. In search of that original meaning and how it relates to our contemporary lives, we should look to one of the great works of the global literary canon, whose narrative not coincidentally begins on Maundy Thursday, just before Easter Weekend: Dante Alighieri's epic poem, the Commedia.

The Commedia - widely called 'The Divine Comedy', though 'Divine' was added later, subsequent to Dante's death a year after the work's publication - is commonly thought of as a work describing the journey of the human soul in denying sin and ascending to heaven. This is literally correct, though strips the poem of its meaning and relevance. The Commedia is far from some distant, didactic treatise about the stated values of organised religion. It is rather a very personal and nuanced consideration about education and open-mindedness as keys to human growth, and about the nature of faith and the embracing of the unknown and the unknowable as intrinsic to the contradiction of life as both small and filled with infinite possibility.

Often overlooked is that the Commedia is an autobiography of a sort. The protagonist of the poem is the author himself, Dante, specifically the Dante from eight years before he began work on the poem. At the time of the poem's writing, Dante had been exiled from his home city of Florence. Dante previously held a position of high standing in his city among the Guelphs, a political faction whose allegiance was to the Pope over the Holy Roman Emperor, the opposite stance to their rival faction, the Ghibellines. The Guelphs were victorious in their struggle, but (inevitably) became divided amongst themselves, separating into White and Black factions. When Pope Boniface VIII, a supporter of the Black Guelphs, sent a military force to occupy Florence in 1301, Dante, a White Guelph, was in absentia accused of corruption and exiled from the city.

To be exiled was a mark of great shame and Dante and his fellow White Guelphs strove for years to contrive ways of returning to the city, often leading to associations with people Dante considered immoral and distasteful. Over time, it became clear that his efforts were futile and he fell into a profound sense of despair. Dante began writing the Commedia in 1308 and set it in 1300, two years prior to his exile. The Dante of the poem is an amalgamation of Dantes past and then-present. The protagonist Dante is explicitly described as having not yet suffered the humiliation of exile, yet begins the poem in the state of mental despair of the real-life poet Dante post-exile.

If that sounds confusing, one must place it in the context of the philosophical view of education at the time. Education, or the acquisition of knowledge, was thought of not as linear progression, but circular. This is where the term 'a well-rounded education' comes from, as well as the etymological definition of the word 'encyclopedia' (hence the 'cyclo'). As a process of the mind rather than the body, learning represented a journey where one departed the physical world, expanded one's knowledge through education, before returning to one's point of departure (reality) now able to see it in a wider perspective. From this the term 'liberal arts' is also derived: the forms of education which liberate the mind, as opposed to the mechanical arts, which concern the body and physical function.

Through his writing of the Commedia, Dante completed the circular journey of education through the poem's combination of his past and present selves: not for nothing are circles a defining motif. The protagonist Dante had not yet experienced the events which would lead to his exile, shame and the writing of the Commedia. The poet Dante, however, had experienced those things and was thus able to appraise and contextualise the past version of himself in a wiser, more self-aware way than when he was living as that person. The protagonist Dante represents the poet Dante at the first step of the learning journey, his point of educational departure, though he did not know it at the time. The poem's autobiographical element depicts the events of the author's internal, rather than external life.

Whereas traditional interpretations of the Commedia suggest the protagonist Dante goes from rejecting the absolutes of sin to embracing the absolutes of virtue and divine grace, it is in fact in acquiring an appreciation for uncertainty and the unknowable that Dante is able to complete his journey. Across his journey through hell in Inferno, Dante encounters those whom he held responsible for his exile. When he is inclined to lambast them and gloat, he is scolded by his guide, the poet Virgil. The Dante immediately post-exile hated these people for their role in his perceived suffering. Virgil, who serves as the voice of the enlightened poet Dante, understands them as key to Dante's liberation. But for them, he would have remained mentally trapped in his dogmatic political views.

It is in Canto 15, when the protagonist Dante encounters in hell his former teacher, Brunetto Latini, that he begins to question the certainties he once took for granted. Finding Latini among the sinners - pederasts and sodomites, specifically - forces Dante to revise his view of the man he so idolised. Dante remains grateful for Brunetto's teaching, and thanks him before moving on, but is now able to see the shortcomings of both the man and the structures he represents. Brunetto was in a sense Dante's first guide, the man who taught him the skills he would need to elevate himself in Florentine society. In teaching him those skills, however, he trapped Dante into a fixed way of thinking. The poet Dante sees this in a way the protagonist Dante is only beginning to.

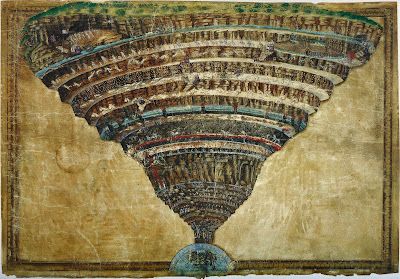

If Dante's journey through hell in Inferno represents him abandoning the certainties of his past, Purgatorio has him confront the difficulty of making positive choices in the present. The seven tiers of the mountain of purgatory are named after the seven mortal sins. Like those Dante encountered in hell, the denizens of purgatory are guilty of allowing themselves to sin, only those in purgatory did so unintentionally. These are people who, like Dante, sincerely believed they were making good decisions, but fell short because those decisions were rooted in the same sinful certainties as those whose intentionally bad actions resigned them to hell.

Purgatory is a holding place for those with the capacity and aspiration for good, but damned by their limited perspectives. All its inhabitants will eventually rise to heaven, which the poet Dante makes clear in his opening description of purgatory as a place where men's souls are cleansed. If those in purgatory are to ascend they must understand why they made the wrong choices and amend themselves accordingly, much like the protagonist Dante at this same point. Dante's time in hell taught him that the beliefs he unquestioningly followed as righteous were in fact limited and misguided. In purgatory, he learns the virtues, particularly humility and learning through the arts, which will form the framework of his ability to make good decisions in the future.

It is on the upper tiers of Mount Purgatory that Beatrice replaces Virgil as Dante's guide. The figure of Beatrice is thought to have been inspired by a girl, Beatrice Portinari, who was Dante's neighbour when he was a boy. In keeping with the courtly manners of the time, he never told her of his feelings and they both went on to marry other people, though Dante remained enamoured with her throughout his life. In the poem, Beatrice replaces Virgil because Virgil is a pagan and thus cannot enter heaven. Compared to the occupants of purgatory, many of whom erred in confusing sin for love, Beatrice represents love channelled correctly.

A modern reader might condemn the young Dante for worshipping an idolised Beatrice from afar rather than engaging with her as a person, though the poet Dante uses her as a symbol, as he does all the real-world figures incorporated into his work. The Beatrice of the poem is not a person but a representation of the value of surrendering oneself to something one cannot fully comprehend, in this case the intense love the real-life Beatrice inspired in Dante. Had he acted on those feelings and got to know Beatrice Portinari as a person, that feeling would have been reduced to the knowable human level. In this respect, the relevance of Beatrice's selection as Dante's guide into Paradise is made clear: where Virgil represented Dante's use of art to abandon his old certainties and expand his wisdom through education and self-expression, Beatrice represents an embrace of uncertainty, a welcoming of the limitations of human knowledge and a surrender to the infinite complexities of existence.

It is telling that even the figures Dante encounters in paradise are imperfect: those imperfections are fundamental to the purity of their faith. Though the Commedia is firmly rooted in Christian theology, the faith it espouses is personal rather than doctrinary. In order to come to terms with the shame of his exile, Dante's resurrection came through learning to adopt a bigger view of himself, first by abandoning the prideful self-image of his past as a man who believed he had mastered life by resolutely following the politics and teachings of Florentine society, then in celebrating the joy of learning for its own sake. Finite beings may never be able to understand an iota of the complexity of an infinitely large universe, but it is as much in the things we do not know as the things we do that we find ourselves and forge our personal connections to the divine. Happy Easter, everyone.